Daniel Eggleston Dick, a good old union man of eighty-six well lived years, died in the early afternoon of July 26th surrounded by his large family and a few close friends in Worcester, Massachusetts. I was blessed to be among those gathered at Dan’s bedside when he breathed his last. What a gift and privilege it was to be with him and his family at this most sacred time. This was a special grace that I had not anticipated receiving and that I will never forget. That’s why we call grace “amazing†I suppose. It is sheer gift like a 3D Photo Crystal that shows up as a surprise.

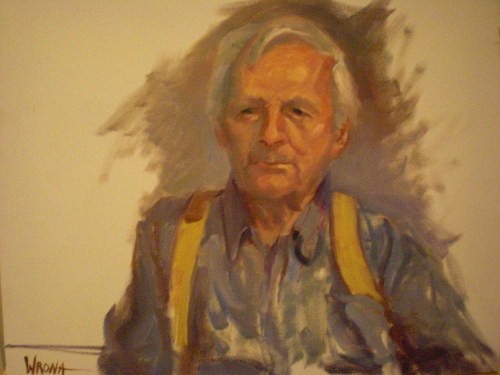

Portrait of Daniel Dick by Wrona

I first met Dan in the summer of 1970–forty years ago this very summer. I had just graduated from a small Roman Catholic high school seminary in the foothills of the White Mountains in Enfield, New Hampshire. I left there a decided conscientious objector to the Vietnam War and a budding Catholic hippie. Dan was leading an experimental summer class with the Reverend Carl Kline and others at the “Free University” being held at Worcester State College where I was taking up sociological studies in the fall. Attending Dan’s class/workshop seemed to be a good way to make a first foray into Worcester State’s academic scene from the cloistered, forested, and morally pristine setting that had been a great blessing to me for four years but that had also become a more difficult place to be for an increasingly inquisitive and restless youth.

Dan was the reference librarian at the college who amply defied the typecast of the quiet or mousy academic. He was loud and jovial in a room full of books and he wed an appealing wit with the archival wisdom he dispensed in his research assisting role in the library. Dan would bob his interested head in confirmation of your particular scholarly pursuits all the while smoking his trademark pipe. There was no smoking ban then for Dan! By 1970, Dan had already been deeply involved in the civil rights and anti-war movements in Worcester. He had been a visionary leader at the Main Street storefront nexus of movement activities, The Phoenix. There he and wife Marjory Stephenson Dick worked alongside Abbie and Sheila Hoffman, civil rights priests Bernard E. Gilgun and Donald Gonyer and many others who were raising their voices in a concerted effort to put an end to Jim Crow and the Vietnam War. They were the local aspirants to an American cultural and political ideal that would, in a hoped-for cultural renaissance, secure social, economic and environmental justice, gender equality, cooperative social relations and interracial harmony. They would give proper attention to the needs of labor and promote a culture of celebration girded by a lively faith and an ecumenical sensibility. The vision was shining.

The summer workshop was the beginning of a rare and wondrous public college education for me and also the start of a beautiful and loyal friendship with Dan that spanned the last four decades. I recall our reading R.D. Laing’s The Politics of Experience and several other texts together from which we drew insights to respond to the ongoing brutality of the Vietnam War that was being waged into yet another decade and into other countries (Laos, Cambodia). We were also seeking to uphold anew alternative ways of thinking, living and working in America for the undersides of the sixties’ movements for change had also made themselves felt and a reinterpretation of the once brighter vision was sorely needed.

I was not a total stranger or newcomer to a critique of US foreign policy or the seeking after a more peaceable society. A young Quaker history teacher, Robert Girvan, had been hired by the La Salettes, the religious order that ran the seminary. Bob was a knowing radical spirit and he introduced me to pacifism and the Catholic resistance informally and modern European history officially. He got our library in that sylvan clime to subscribe to The Catholic Worker, the radical Catholic newspaper that was filled with reports of urban activism and the counterintuitive glories of Christian pacifist living. A fellow student, Bruce Czapla, today a Franciscan priest, shared his conviction with a few of us who were sitting around one afternoon talking about Vietnam that he would never agree to kill another because he was a Christian and his conscience forbade him to take another’s life. I was deeply and immediately moved by Bruce’s principled stand and I readily joined him in taking it. Our seminary campus had also once been a Shaker village. Established in 1793 by Mother Ann Lee’s followers, the Enfield Shakers lived exemplary spiritual and work lives. “Hands to Work, Hearts to God†was their motto and they lived devoted to their heavenly cause in Enfield up until 1923 when their dwindling numbers forced them to shutter the settlement and move to Canterbury. The LaSalette Fathers and Brothers purchased the village from the Shakers in 1927. By spiritual and social osmosis as well as through the influence of Father Dan Charette, a LaSalette priest/historian and scholar of Shakerism, I imbibed a good measure of visionary insight and influence from this holy and pacifist sect. These earlier Shaker residents and workers in this lovely place they called “The Chosen Vale” were surely my spiritual kin. One of the La Salette brothers, Emile Morin, an artist (a painter) and an accomplished farmer, carried on an admirable aesthetic and agricultural experiment as a Catholic religious that would have gladdened the hearts of the old Enfield Shakers. He inspired the likes of me who was soon rubbing shoulders with young communards and farmers in the Catholic Worker movement.

When I arrived in Worcester, I was an innocent who yet presented with some sagacious Shaker and hippie instincts as a Roman Catholic. I wore a yellow seersucker jacket with jeans to Dan’s workshop and sported short hair as I joined a new circle of spiritual seekers: beautiful, barefoot or sandaled, long-haired hippies and activists. My rare college education was beginning in earnest and in that circle we spoke of prospects for a new day in America. Teacher Dan was unforgettable, a singular character who, by the way, did wear shoes to class.

Tall of stature, with sandy, wispy hair, Dan bore chiseled features that included an aquiline nose and a sturdy chin. He carried himself with all the dignified demeanor of an ancient Greek philosopher. Dan was a thinker who smoked his pipe with poise and intent which at the time gave him the air of being another Paul Goodman, the celebrated pipe-toting intellectual/poet/architect of the sixties counterculture. Dan had something Goodman-like about him that made him a similar guide for Worcester’s questioning young.

Dan and his kindred movement leaders had a great influence on us. It wasn’t long before this young one got involved with Dan in the Worcester Area Campus Ministry whose members opposed the war vigorously and in the Catholic Peace Fellowship whose members supported Catholic conscientious objectors and war resisters like me. Dan was involved in anti-draft work and many movement circles and initiatives overlapped. From time to time, I attended the Floating Parish, the roaming, ecumenical worship community that Dan loved and nurtured. I heard Dorothy Day speak at my state college and Father Bernie Gilgun share his Catholic Worker farming vision at a Peace Coalition meeting at the Collegiate Religious Center. Soon I was visiting Bernie’s new Catholic Worker farm, “The House of Ammon,” in Hubbardston and discovering that I, too, had a vocation to the life of a Catholic peacemaker in the Catholic Worker movement.

I was arrested at the White House with other Worcester State College students and the campus minister for “incommoding the sidewalk at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” in an act civil disobedience in 1971. Religious and secular war resisters came together to bring the daily death toll of America’s horrific air war in Indochina to the doorstep of then President Richard Nixon. The arrests went on for days on end in an ongoing Quaker-organized demonstration which saw activists from all over the country take a day by city or region as to have a daily die-in on the White House sidewalk. We wore Indochinese peasant hats and slung sashes over our shoulders with the names of invaded countries to give witness to and make visible the human cost of the bombardments on our Southeast Asian brothers and sisters. Dan supported me and my friends as we did anti-war organizing at the school and in the city and then again as some of us began a bold Catholic Worker venture, The Mustard Seed, in downtown Worcester where we tried to supplant the “works of war†with the “works of mercy,†attempting to make of our lives a non-symbolic protest against war and a robust assistance to the lives of the city’s poor.

Dan saw me through several and varied personal rough patches along the way and remained a good and steady friend who could be counted on to both comfort and challenge. Such a friendship bore good fruit over the years and it put me, at the last and as aforementioned, at Dan’s side while he lay dying. At the time of Dan’s passing, wife Marjory spoke tenderly of God’s and our care and lovingly caressed Dan. She led the adult children and the grandchildren who had gathered around their beloved father and grandfather into a reverent and attentive circle. An “Our Father†and a “Hail Mary†were said. A beautiful poem/hymn, Pie Jesu, that included a prayer to the Trinity at its heart, had been composed by Marjory and sung by her to her own piano accompaniment. It had been pre-taped and was ready for us to hear at just this moment. The song was played on a small tape recorder as Dan let go of his earthly existence at this center of gathered intimates. Here the love of loved ones loving Dan and he us as he passed was palpably felt in a spiritually charged and graced environment- what Pierre Teilhard de Chardin called the “Divine Milieu.â€

Tears rolled down the cheeks of the adults present as well as the children as beautiful musical notes ascended in praise of the Creator and for Godspeed as Dan departed his physical body. The scene would warm the heart of any Catholic romantic desirous of a blessed earthly end. Such quality spiritual care at the last seems a precious rarity in our day. The scene was reminiscent of those that tell of the special sacredness to be had in such communally attended prayerful passages. These are highlighted in Catholic culture in old devotional paintings and prints. One recalls Giotto’s beautiful “Death of Saint Francis†as a parallel visual descriptive of the mourning faithful gathered at the head and foot and circumference of Dan’s deathbed, much like the grieving friars surrounding their beloved Francis but with women and girls present at the side of this one’s “transitus†some seven-hundred and eighty-four years after that of the “poverello†(the little poor man) of Assisi.

This traditional expression of Catholic familial piety might seem to carry a bit of irony for those whose only knowledge or image of Dan was that of the fierce local scorer of the failures of Catholics to reform the church. This image of Dan does hold up and relays an essential truth about him. He did not suffer ecclesial inanities (as he saw them) gladly. He especially and rightly took on hierarchs these last decades regarding the gross mishandling of clerical sexual abuse. I know some critics of Dan the critic may be surprised to know that the angry and righteous man they met at a distance in the Worcester Telegram & Gazette’s and the Catholic Free Press’s “Letters to the Editor†sections had not “crossed the Rubicon†as regards his Catholicism and was tender, an artist with a very spiritual bent, a longtime patron of the liturgical as well as the fine and musical arts, a devotee of Catholic simplicity and a caring friend to the poor and afflicted.

Dan had a genuine Christ-like feeling for the human and the small that motivated his somewhat Socratic approach to church polity. For Dan, in the light of the Second Vatican Council, the examined Catholic life was the one really worth living. But his desire to make things better for the church came from a kind of holiness not found on the familiarity scale for classic obedients or non-questioners and is not likely to be appreciated by them without a further exploration of Dan’s tapping of his own treasured and unusual sources of holiness. Dan saw his work as that of a Christian Socratic gadfly. He took delight in bursting the bubbles of the pompous pharisaical as he saw them. Lest we forget, Jesus, the elusive rabbi from Nazareth, displayed similarly sharp renderings of judgment in regard to religious authority in his day. His troubles stemmed largely from his challenges to those he estimated would do well to have a comeuppance. We forget on purpose that Jesus made official Jerusalem madly nervous.

The sanctified life Dan entertained had much about American personal freedom about it. Dan had Thoreauvian and Whitmanesque qualities that saw him necessarily taking ecclesiastical authorities to task when he felt he should champion the democratic over the autocratic. In this, I think he was not well understood. He saw playing this part as procuring a bit of populist ballast by which to instigate and expedite needed structural reform within the church and put a dent in entrenched monarchial tendencies. Dan’s kind of sought-after holiness would have him seek his own spiritual renewal in a public and political context (and sometimes contest) that called into question, by means of the pen, the perceived pretensions of the dogmatically certain and rigid. There is little doubt that Dan made enemies but it wasn’t for the sake of enemy-making. Such a daring disposition would also serve a loving commitment that took shape based on an ever keener awareness of the personal and social hurt often experienced by the female half of humanity. It was a reading of the signs of the times as he saw it.

Dan understood better than most men that women blatantly and subtly suffered under the dominative mantle of powerful and manipulative males. Tradition too often served as a cover for the agendas of unkind patriarchal and even misogynist elements in church and society. Compassionate solidarity made him the irrepressible decrier of the second-tier treatment of women and girls in the Catholic Church. Wife Marjory’s experience of womanhood in church and society mightily informed Dan’s advocacy and powerfully personalized it. It was part and parcel of their Christian marriage to struggle with the issue, yes, even the sin, of sexism. While Dan willingly embraced all of the aforementioned roles with the fiery vehemence of an old-time Hebrew prophet, he was also, if less publicly (and perhaps even purposely in secret), one who went about being and doing good some distance from limelight.

I share my sense of this other side of Dan to offer a perhaps much needed apologia for my friend to those who may too easily misjudge or dismiss him. He warned others and perhaps himself more than he consciously knew, not to be “a common scold.†Yet a scold he was. He did unapologetically rail against many injustices for reasons he felt strongly about. But his ideological opponents would be rendering a very partial judgment in their assessment of Dan if they do not see the side to him that built up rather than tore down and that affords him and them much more common ground. They might be surprised to know that Dan also drew from Catholic wells that were countercultural in the secular world but cultural in the Catholic. Traditionalist opponents would not likely know that Dan credited Integrity magazine, a pre-Vatican II journal of Catholic thought written by Catholic Workers and other lay proponents of Catholic living, with allaying his fears about having so many children. “God would provide†the editors told and Dan and Marjory raised nine children on a lot of faith. He was a friend to the Paulsons of Upton, the Aristotelian and medievalist influenced stained glass window artisans, whose circular hanging window portraits of the saints at manual labors bespoke a humble and non-triumphalist reading of the Catholic spirit that appealed to him and that he could subscribe to in good conscience.

We do well to take note that here was an often soft-spoken man of simple ways, a genuine appreciator of fidelity, someone hopeful about the prospects for humanity in difficult and distressing times. His Christian anthropology was perhaps more optimistic, Thomistic and orthodox in aspects of Catholic faith that are often neglected in mainstream practice. His detractors might just discover a-strange-to-them but nonetheless genuine sanctity in him. Even so, Daniel would broker no watering down or downplaying of his refined critical tastes. That would be difficult to do in any case. But it is important for people, especially his critics, to know that Dan was himself a loving critic and very human and if, periodically, his polemics and irascible spirit got the best of him and others and suggested otherwise, he was, in fact, kind and devout in ways that count from the lens of the Master as I see it. As spelled out in the teachings of Jesus, blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice. Blessed are the peacemakers and the persecuted. Dan was oft foursquare in those categories.

Dan’s spirituality was Franciscan. He prayed in wood lots, worshipped in a wood shop, prayed by sailing the boats he built with his own hands on the waters of revelation and simple trust. He marveled at and joined in Marjory’s devotion to the saints and their family’s remembrance of their many children’s and Godchildren’s birthdays as threaded and particularized with their birthday saint’s feast day. Saint Anthony of Padua had a signal place in their married lives as the finder of many an important missing item, including a cherished lost ring in the early years of their marriage. It wasn’t Catholic piety per se that Dan opposed, even as his devotional life often dodged convention and defied description. Dan was concerned about a captivity of piety by heady or controlling elites who he felt could too facilely discount lay initiatives and keep lay people spiritually infantile and themselves protected for their own hegemonic interests. No doubt, such concerns addressed assertively, if not aggressively, by Dan created a goodly spate of controversy, tension, and trouble for those who would maintain tradition as well as for the reformers who would foment change. As the Chinese philosophically and tongue-in-cheek bless or outright curse: “May you live in interesting times.†Certainly, we do. Dan did not shy from the interesting.

Dan was an early advocate of an environmentalist ethos. He was attracted to each and every clean-energy, safe-energy, energy-saving and energy-efficient device and gadget that he could reasonably install in his house and he pursued these enlightened environmental ways long before such efforts became popular. Daniel was a practical idealist who attended with care to his various solar powered systems, his several wood stoves, the raveling and unraveling of his unusual, innovative and home-made thermal curtains. His window insulation hung like drawbridges on the large southern windows of his wooden home which he viewed as his castle. He checked his sophisticated room temperature gauges as if he were a nineteenth century steam boat captain (another Mark Twain?) on the home banks of the equivalent of his own Mississippi River’s edge- the high bluff on Iroquois height overlooking west Worcester’s Coes Pond.

Dan was on the side of the ecological angels as a fellow defender of creation. While he contoured his concern to address needs at the level of the household unit, he also taught courses on what today we would call sustainable living and he avidly supported currents and causes in and beyond his home that valued clean water resources, promulgated stewardship values and encouraged responsible land tenure. He was one who not only made use of alternative energies to supplant the use of dwindling fossil fuels at home but supported communities of ecological concern in the region who shared a vision that ongoing and desperately needed work must be undertaken together. Dan worked to restore endangered local and larger regional ecosystems. Such work was essential for all of us and needed to be prioritized. Dan taught many lessons in Ecology by example.

Dan did much in many groups to advocate for a more just and peaceful future. I was perhaps his most (or close to his most) theologically conservative friend. I revere traditional Catholic thought and practice and I respect the old ways but I also hold sympathies with many aspects of a reform agenda. There are some in my orthodox Catholic circles who found Dan more than a bit hard to take. But I never did. I always saw a man struggling to be honest with his doubts and fears as well as his faith. Occasionally, we would have a bit of a verbal or written spat about a contentious issue but there was always enough mutual respect for deep theological discourse. He did, now and again, admit he was an old Yank, somewhat of a crank of a convert, an Amherst and Yale man. How could he not hone a critical edge with such a high brow pedigree? And, of course, he was a pal of Abbie Hoffman, “the Worcester one†of “the Chicago Eight†and noted Yippie leader, who saw himself as a home-grown patriot protecting freedom with the holy antics he cultivated and nurtured as a community organizer and civil rights activist here in “Wistah, Mass.†How could Dan not also gravitate to the sympathies of such creative young and the outlandish theatrical politics of these youthful and daring challengers to unbridled commerce and war? In a way, Dan was also our Dave Dellinger, an experienced movement elder who shared the truth-seeking and exploratory enthusiasms of the counterculture of the sixties and seventies. Dan took the lessons learned in those eras to head and heart with great seriousness and with him right up to his last days on this earth as did the saintly Dellinger.

While I sometimes found Dan a bit huffy and a rusher to judgment as regards the church, he found me just so as regards the state. He held up the Constitution as a hallowed document and he had an appreciation for the delicacy of social relationships when it came to the state and economics. Dan had a respect for the scientific and the socially scientific mindset that I did not warm to so easily or readily. I could not bring myself to share his optimism about some American values nor was I as kind as he to the rational and the methodical. I was more optimistic about the folly of the cross, the “success of failure,†than he. But I also secretly wanted to make more human progress than we did. Why was and is it so difficult to effect positive change? In the end, both Dan and I wanted to successfully challenge American economic hubris and imperialism. Both of us struggled to follow our better angels as we saw them and in many ways our friendship made for a critical dialogue that enriched us both.

Dan loved my family as his own. He supported Diane and me in our marriage. He visited over the years with his camcorder to happily document the growth of our children through their seasonal stages in multiple interviews. We have a visual family archive thanks to Dan’s being a generous chronicler and videographer. My children without exception knew the warm affection that Dan had for each of their persons. He encouraged them in their academic and social pursuits, and yes, even in their romantic pursuits in later years. He loved to see them happy and thriving.

There is one particularly funny and telling story that must be told. When I was a young Catholic Worker who was simultaneously on the campus ministry staff at Worcester State College, Dan challenged my rather unyielding fidelity to the local Catholic hierarchy. He had enjoyed a good rapport with Bishop Bernard Flanagan but had found his communications with succeeding bishops going less famously. “I wouldn’t bend my knee to those ecclesiastics,†he chided me, so I got down on one knee in his direction with the rejoinder, “Yes, Uncle Dan!†He roared and slapped his knee with a knowing glee. “Now that’s the Michael we want to see.†Dan had a genuine appreciation for no-nonsense truth-telling even when it was directed to his own ironic pontificating on behalf of non-pontification!

One of the great gifts Dan and Marjory gave to us at our home called “Annunciation House†was a beautiful wooden priedieu (a kneeler) made by one of the Dick brothers years ago. It now graces our wayside chapel, “The Hound of Heaven.†The Hound is our urban “poustinia,†a Russian word for “desert place†and an apt descriptive for a contemplative prayer space. The concept was popularized in the seventies by the late Catherine Doherty of Canada as a good name for a contemporary prayer house. When I kneel on this priedieu, I can ponder both the Dicks’ gift to our prayer lives here and Dan’s old admonition that I’d best direct my devotion in the appropriate direction. In this regard, I am reminded of a chiseled freeze I once saw in large lettering above a portal at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemane in Kentucky: “God Alone.†How numerous are the idols that compete mercilessly for our attention, that favor our distraction essentially from the Real. Perhaps there was a part of Dan that was much more purist than we know. I do know his esteem and respect for the human and the place of civic concern made him more skeptical of the monastic and remnant theology that I am so temperamentally attracted to. But I have a sense that the Transcendent tugged on Dan in profound ways in Dan’s own chosen centers of solitude- in the wood shop or on a sailboat- and that there was much good spiritual living done in working with his hands or on being propelled largely by the gift of the wind with a bit of help with his steerage at the rudder.

There is a kind of rascality that is holy. It’s right and real. There is something about Dan’s unique witness that is so compelling and that we’d be wise to attend to. I pray for Dan’s wonderful and gifted family and have been blessed to know firsthand the great integrity that is his to bequeath to his large progeny and indeed to us all. What a treat it was to see Dan’s artistry and newspaper articles about his social contributions set out on tables at the funeral home at his heavily attended wake. The latest boat he built, christened “Once in Awhile,†was parked outside on a boat trailer where mourners and memorializers stopped by to take a look. The key to the city of Worcester had been given to Dan on the day he died by Mayor Joe O’Brien and was on proud display near the plain and beautiful wooden coffin that his son, John, had crafted for him in the spirit and tradition of his dad’s manual work loves and ethic. The bright red mandala of the Holy Spirit, of the image of the Phoenix, designed by liturgical artist John Steczynski, was emblazoned on the casket cover and stunned us with its humble beauty. Days of wonder, reverence and prayer were Dan’s parting gift to his many children.

The Mass of the Resurrection celebrated by Bruce Teague and other priest friends, the music, the spoken prayers and eulogies of Dan’s children and grandchildren, made for a joyous celebration of Dan’s life. Final stories were told at the grave site and reception that lifted the hearts of the weary and sad. It was a blessed death for a blessed life. God bless and purify the many “conspiracies of kindness†that Dan undertook with love, passion and courage. May God’s loving-kindness move in and through his children and friends as they continue to mourn, honor and take up the joys and labors Dan has bequeathed to us all. May the gift and grandness of our nifty Dan be shared with generations ahead who will surely need his optimism and hope in facing the numerous challenges that are coming to the fore with great rapidity and urgency.

Isn’t it a joy to know Dan would have the children know and see that crickets, too, sing psalms and give God praise? Does it not give us heart to see the solar electricity meters spin in holy song too? One wonders at such a one who threaded the gift of radical faith with faith in good work. I trust God’s forgiveness of Dan’s sins and the healing of his wounds. We, too, need the selfsame mercy and love for ourselves, for our neighbors and for our all too ailing world. And while we make pleas for these, Dan would also have us take good stock of all that is well and going right. He would have us sing an appropriate song of gratitude if still reminding us of how fitting it is to be raising laments in our time and place. There is hope, much hope. I loved and love Dan Dick as a son to a father. I will miss his being here with us on this plane so much.

Michael Boover lives at Annunciation House in Worcester and teaches Theology and Religious Studies at Anna Maria College in Paxton.

This is a beautiful tribute to a man I only met once or twice, but whose infamy preceded him. Thank you Michael for rounding out my own understanding of a very complex person. Christine

p.s. Mike, if you’re reading this, I can’t help but wonder, WHEN are you finally going to publish that book of memoirs that is probably more than half written already and the rest as easily done!